If you’re in the market for life insurance, let me tell you something you already instinctively know: term life insurance is more expensive than whole life insurance. And not by a little.

It’s a lot more expensive.

Meanwhile, whole life insurance is not only more cost effective over the long-term, it has an excellent rate of return on cash values given its risk profile, and it’s been proven through independent research by Ibbotson and Morningstar to reduce the overall risk of a diversified investment portfolio without significantly compromising total investment return.

A lot of this has to do with how the charges for both term and whole life are assessed and how whole life insurance cash values build up inside the policy.

The high cost of holding term insurance for the long-term seems absurd on its face since the only message you hear from pundits and the mainstream financial media is:

“Term is cheap!”

But, the exact opposite is true.

If anyone doubts this fact, they only need to observe policyholders dropping their coverage after the level premium period ends because the cost of insurance skyrockets.

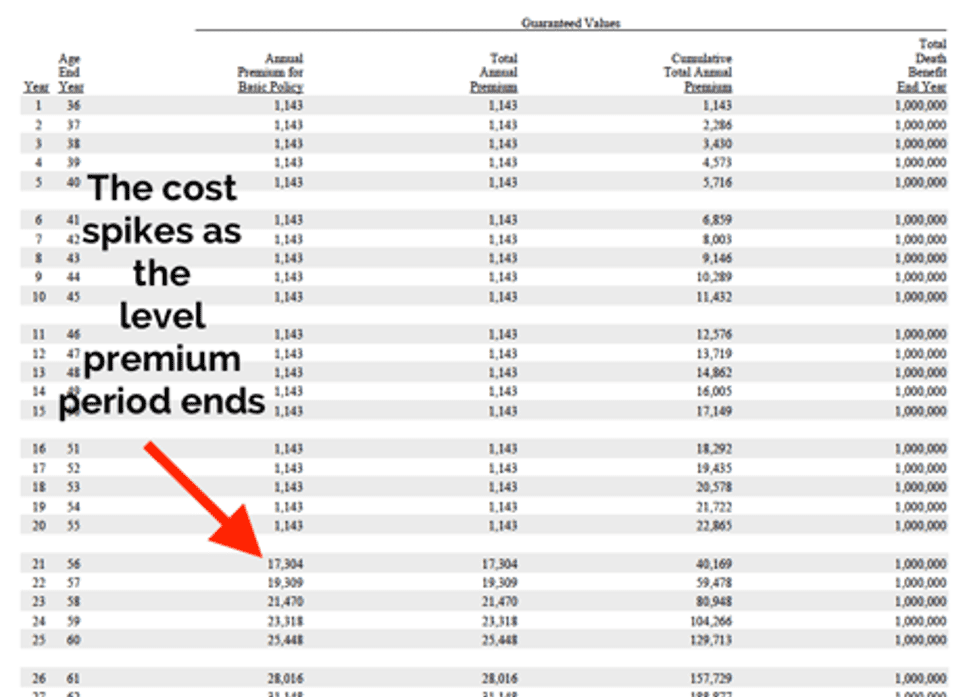

Here’s what that looks like:

This is a quote for $1 million of term insurance for a 35 year-old male, standard, non-smoker, from a highly-rated life insurance company.

Premiums start at $1,143 per year and after 20 years, the premium jumps to $17,304 — an over 1,400% increase. Most level premium term insurance policies sold today work exactly the same way.

The insurance company rigs the policy so the lowest premiums are bunched up in the early years of the policy when the insured is least-likely to die. Later, premiums rise to make up for artificially low premiums in the first 20 years.

The result is a policy which is initially cheap but which becomes very expensive and ultimately lapses, unused.

About the alleged simplicity of term insurance, life insurance companies must combine 2 different types of policies to create this auto-renewal “feature.” And, in doing so, they create an inherently complex insurance product, complete with an array of riders and benefits — all of which have a profound effect on the outcome of an individual’s long-term financial plan.

Still, the myth of cheap term insurance persists.

Underneath this veneer of cheapness lies the true problem of term life — the savings component. Namely, there isn’t one that is easily discernible. Although, unbeknownst to most insurance professionals and financial planners, there is a way to extract cash from the policy. More on that later.

Most advocates of term insurance are quick to argue this is a feature, not a bug. But, statistical analyses and some relatively uncomplicated math proves otherwise.

Another popular, related, argument for term life insurance is that when the insured dies, their beneficiaries get both the term death benefit and their accumulated savings.

Claim up to $26,000 per W2 Employee

- Billions of dollars in funding available

- Funds are available to U.S. Businesses NOW

- This is not a loan. These tax credits do not need to be repaid

True, but most people outlive the term, so these hypothetical benefits rarely, if ever materialize. Consider if term payouts were routine, and people really were beating the life insurance company at its own game, then the profit motive would prevent such low premiums from being priced in the first place.

Insurers would hedge against its customers leveraging the insurer for profit.

Back in reality, life insurers rake enormous profits from the sale of term life insurance and customers are happy to pay for the privilege of protection, but… most policyholders outlive their term to fight the Grim Reaper another day.

This is both why term premiums are cheap for the first 10-20 years of the policy and why most beneficiaries never realize the dual benefit of receiving the death benefit and savings after the death of the insured policyholder.

Of course the critics argue policyholders get cheap premiums when they need them and that people don’t need term insurance after 20 years because they’ve saved up enough to eliminate their need for term life insurance by the time they retire.

In other words, proponents of what has become known as “buy term and invest the difference,” argue that a typical investor can save up enough money to replace their term coverage by the time the level premium paying period on that term insurance policy expires.

To state it yet another way, most proponents of a “buy term and invest the difference” strategy believe the average person can beat the life insurance company at its own game.

But, is this true?

Do any, or even most, people beat the life insurer?

Does it make any logical sense that an untrained, non-professional, could easily beat a collection of the best minds in actuarial science — experts in risk and investment portfolio management?

Let’s think seriously about this for a microsecond. Andy Bolton was the first man to deadlift more than 1,000 lbs. To date, no amateur powerlifter and no untrained individual has beaten his record or even come remotely close.

And most people, who have no desire to become a professional powerlifter, intuitively understand the futility in trying to lift Andy-Bolton-sized weights without becoming a professional.

You see the same problem in technology. If it were easy to beat Google or Facebook at its own game, why isn’t the world littered with tech entrepreneurs creating Google and Facebook clones?

If it were that easy to beat doctors at their own game, why isn’t everyone a medical professional (the proclamations of Food Babe notwithstanding).

But when it comes to insurance and investing, and indeed most areas of finance, suddenly everyone is an expert with little more than “tender” Google searching and without actually having to be an expert. And indeed, the Internet is full to the brim with self-proclaimed insurance experts running “mom-and-pop” blogs, proclaiming the truth bestowed upon them by A.L. Williams and Dave Ramsey guru clones.

They come to the Internet, armed with a smattering of factoids but no real training (formal or otherwise) in insurance. They rush to give their friends and strangers financial advice, despite the fact that they themselves hold contradictory premises and illogical opinions.

They proclaim, without serious proof, that “whole life insurance is a scam” and that term insurance is “simple and cheap,” despite the fact that both products carry similar mortality costs over the long-term, but only whole life reduces those costs through systematic reduction of the pure insurance component of the policy while term insurance assumes the policyholder will either lapse the policy or spend accumulated savings to keep the insurance in force until death.

The problem with the latter assumption is that investors, as a whole, don’t earn the double-digit returns touted on personal finance blogs. Instead, most people, most of the time, earn far less than the “12% reality” or even the “8% reality” advertised on the Internet.

They also tend to save less money than what is actually needed to replace their term insurance. And, when they do save, they must save money each month out of their paycheck, as they earn it because they don’t have the luxury of investing money at the beginning of each year before they’ve actually been paid.

This creates a natural drag on investment performance — a minor detail practically no one talks about — because for roughly half the year, half the contributions an investor will make to his savings remain uninvested until he earns them and is able to invest them.

If anyone doubts any of this, one need only “run the numbers” or better yet… study the history of such attempts to beat the insurer using real price quotes for actually-existing whole life policies as well as pricing data for investments

According to studies from Morningstar, Vanguard, DALBAR, and others, most investors earn just somewhere between 3% and 6% on their investments, before taxes (not counting the drag created by paying term life premiums). And, despite what you read on the Internet, not even low-cost index funds have saved people or made them fabulously rich, and certainly not without taking significant risks.

One has to wonder why people aren’t realizing the gospel of 8% compound annual returns year-after-year for 20 years, much less the “12% reality” promoted by financial experts, like Dave Ramsey.

Some speculate that investors are irrational, entering and exiting financial markets at inopportune times — in other words, buying high and selling low.

There’s even a famous study purporting to show that this phenomenon is real, called the DALBAR Quantitative Analysis Of Investor Behavior.

Even if investors were completely rational, they wouldn’t escape the fact that professional investors with decades of experience have trouble consistently beating market averages under optimal circumstances.

Make no mistake. It can (and by the definition of “average” must) be done. But, it takes skill.

Warren Buffett is perhaps the most skillful and successful investor alive, averaging 15% per year over year for the last 55 years of his career.

Do the Dave Ramsey’s of the world honestly believe that individuals who go to financial seminars because they have trouble with basic budgeting concepts have any chance of beating these investment professionals?

Let’s be real.

Before his death, Jack Bogle, founder of Vanguard, estimated the market would return around 6 or 7% per year for the foreseeable future. He, and many others, believed it will be very difficult for most people to consistently beat that average year-after-year.

Perhaps an investor can score a big win here and there. But, that’s very different from being a heavyweight champion investor.

The advocates of “buy term and invest the difference” (and their followers) are living a fantasy. And, it’s an expensive one they won’t easily recover from, if they ever do. But why, then, to financial planners and some life insurance agents recommend term life insurance over whole life?

There is one reason which defies the narrative that term is cheaper and that is… term insurance is easier to sell. Understanding how to design and customize a whole life insurance policy for a client is terribly difficult for the advisor. It requires real technical skill. It requires ongoing policy servicing. It requires the agent be more than “just a life insurance salesperson.” Commissions for whole life drop dramatically after the first year a policyholder has his policy, and yet the agent must commit 20+ years to servicing that policy.

With term insurance, hardly any servicing is required. In fact, if term life insurance rates drop the year after an agent sells a term policy, he can “resell” that policy, generating more commissions without incurring more service work or long-term service commitments. It’s an ideal situation where the life insurance agent makes virtually no commitment to his policyholders and still gets to earn a living. The burden of policy servicing can be shifted almost entirely onto the issuing life insurer.

It’s so easy.

And, since doing things the easy way pays the bills just as well as doing things the hard way, most life insurance agents and advisors don’t bother actually learning the fundamentals and intricate details of how life insurance really works and thus… they dismiss whole life insurance because… it’s easier to do than understand how it works.

Don’t fall for it. Demand your agent do an honest analysis of term and whole life insurance or… go get yourself a new agent.

Author Bio

David C Lewis, RFC is an independent life insurance agent, a Registered Financial Consultant, and the founder of Monegenix®. For more information about his unique approach to life insurance and financial planning, go to www.monegenix.com.